The Science of Spiciness

Is bland food really that fun to eat? While some may appreciate it, most people tend to crave more flavour. So, to find joy and satisfaction in our lives, we often turn to new experiences and flavours beyond our usual routine. One of the most popular substitutes? Spicy food. Nearly 95% of people globally enjoy some level of spiciness in their meals, a staggering proportion of the world’s population. But have you ever wondered what makes food spicy? What is it that gives that fiery rush that people love? The answer is quite simple yet intriguing.

It all starts with Capsaicin, a chemical found in spicy foods, synthesised by plants as a defence mechanism to fend away predators—ironic how something designed to deter is something we seek out for our taste buds. Discovered in 1492, during his voyage to the New World, Christopher Columbus came across this region, nestled along the Andes in western to northwestern South America. The source of Capsaicin was from the wild Capsicum, which were small red, round, berry-like fruits, thus the name Capsaicin.

So how does Capsaicin work? Well, the science behind it is quite simple. Capsaicin is responsible for affecting the TRPV1 receptors, the receptors behind the sensing of heat and sending pain signals to the brain. The receptors usually send signals after a certain threshold of temperature, which normally lies around 42°C, serving as a deterrent to stop people from consuming stuff that’s too hot. The fascinating thing capsaicin does is that it lowers that threshold to nearly 37°C—which just happens to be the average human body temperature, fooling the receptors to send signals of pain to the brain. This makes us experience a fiery sensation on our tongue as if we've put fire on it. However, this is just an illusionary side effect from the confused neural receptors—there is nothing actually "hot" about spicy food.

We, humans, feel different levels of “spiciness” from different sources. This is due to the difference in the amount of capsaicin present. In 1912, a pharmacist, Wilbur Scoville created a scale to measure the pungency (spiciness) of chilli peppers, which measures the amount of spiciness experienced due to the amount of capsaicin. At the bottom, we have Bell Peppers with 0 Scoville Heat units while pure capsaicin can reach a whopping sixteen million Scoville Heat units.

But fear not—there’s a natural remedy for that immense heat: Casein, the primary protein found in cow’s milk. Casein acts as a detergent of sorts, binding to Capsaicin and washing it away, just like soap removes grease. That’s why a glass of milk can feel like a saviour after a particularly spicy bite.

Humans have a unique love for tangy food, unlike most animals that avoid the burning sensation. Whether it’s for the thrill or the bold flavours, we’ve made spice a key part of global cuisines. Our willingness to embrace the heat mirrors our adventurous spirit and passion for exploring new experiences. So, the next time you feel that blazing sensation, take a moment to appreciate the intricate chemistry behind our enjoyment of such bold flavours.

Similar Post You May Like

-

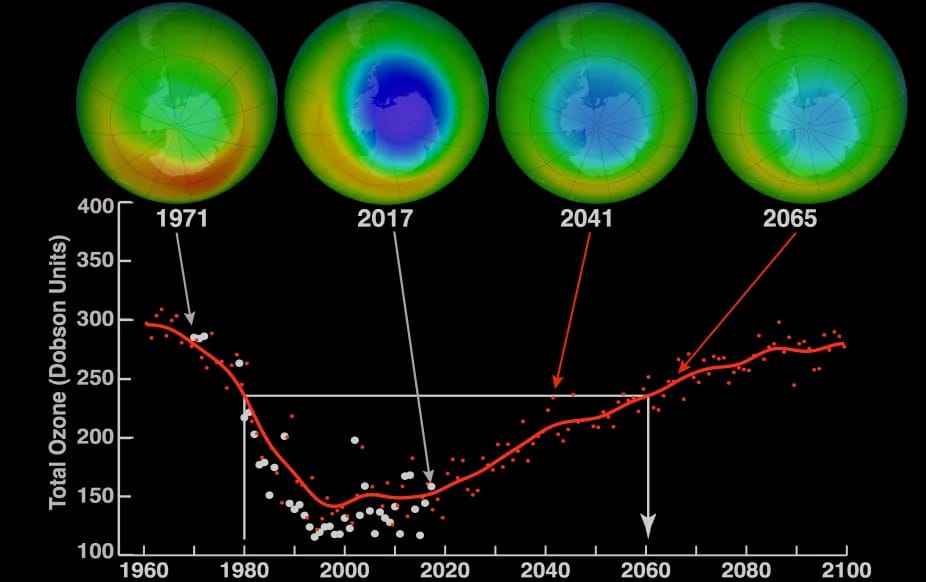

CFCs, HFCs and their long, troubled history

At its peak, the ozone hole covered an area 7 times larger than the size of Europe, around 29.9 million km2, and was rapidly expanding

-

The Origin of Universe: Deciding point where it all began!

Let us unravel and surf through the ideas throughout ages to understand what the universe and its origin itself was to its inhabitants across history.

-

The Artemis Program

Inspired by the Greek goddess of the Moon, twin sister to Apollo, the artimis program was named on 14 May 2019 by Jim Bridenstine.