Bacteriophages: Nature’s Tiny Predators

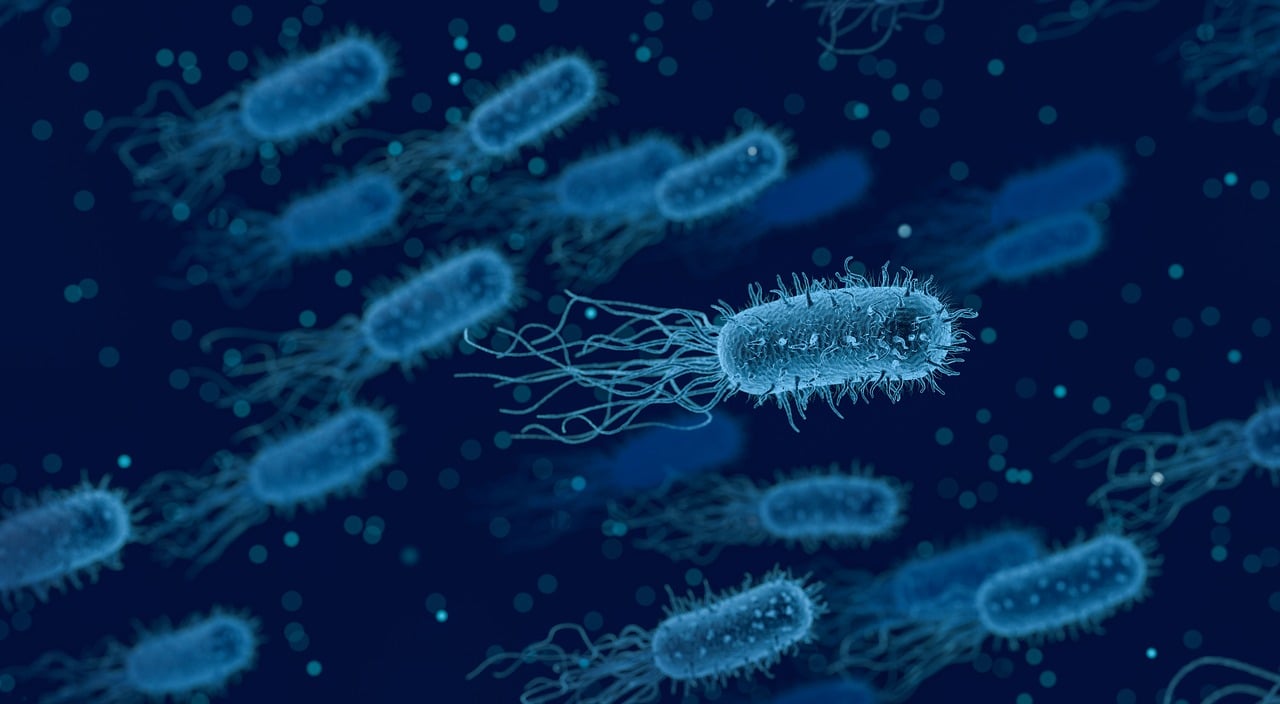

Bacteriophage, or bacterial virus, also known as the bacterial eater, is a microscopic organism that, unlike other viruses, needs bacteria to perform its function. This piece of art was first discovered independently by two scientists, namely Frederick Twort and Felix d'Herelle, in 1915 and 1917, respectively. Felix d’Herelle came up with the term bacteriophage. Bacteriophagage was derived from two words: first, "bacteria,” and second, the Greek word "phagein,” meaning "devour.” Ultimately, it is defined as a virus that kills bacteria.

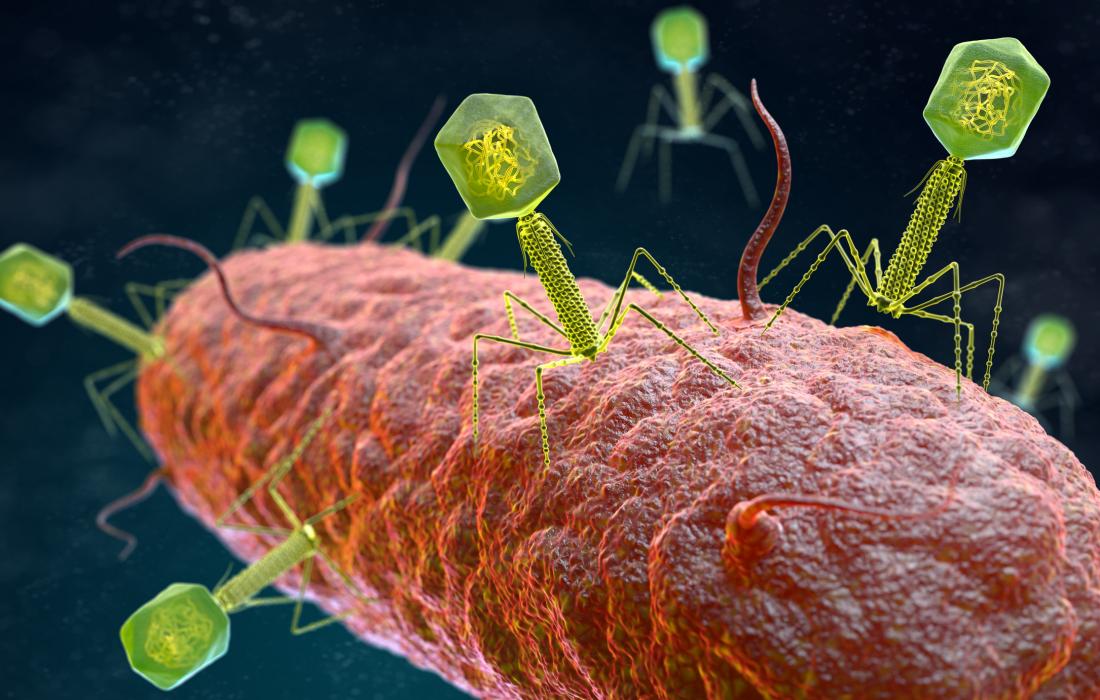

Bacteriophages, like other viruses, are composed of a core of genetic material (nucleic acid, either DNA or RNA, or single-stranded or double-stranded) surrounded by a protein coat (capsid) made up of subunits called capsomeres. The capsid is shaped as a polyhedral head and further attached to a long tail. The tail consists of two parts: the collar and the sheath. Sheath contains a tail tube and provide a pathway to the delivery of genetic material into bacteria. The sheath is attached to the baseplate. Spikes and tail fibers are attached to the baseplate. Tail fibers are responsible for the reversible attachment of bacteriophage to the host (bacteria).

Bacteriophages infect bacteria in two cycles, namely the lytic and lysogenic cycles. In the lytic cycle, the bacteriophage first attaches to the bacterial outer membrane and then releases the enzyme to make a hole in the outer membrane of the bacteria and insert its genetic material. Once genetic material is incorporated into the bacterial cell, the phage takes control of the bacterial cell’s protein synthesis and DNA replication machinery. Phage then forces it to express its own genes, produce its own proteins, and replicate the DNA or RNA. The newly synthesized proteins and genetic material assemble into phage particles, and a total of 200 phage particles are produced in a cell in a very short period of time. As bacterial cell swells up, it bursts open, releasing the bacteriophages, which then infect other bacterial cells and repeat the cycle. In the lysogenic cycle, the genetic material of phages doesn’t take control of the bacterial cell; instead, it incorporates into the bacterial cell chromosome and lives there peacefully, becoming dormant, being passed on to each daughter cell, until it detaches itself from the bacterial chromosome and starts the lytic cycle. The change from the lysogenic to the lytic cycle is caused by many factors, including environmental stress, starvation, or exposure to toxic chemicals.

Bacteriophages have the potential to overthrow the use of antibiotics. When it was discovered, experiments were done to use bacteriophage instead of antibiotics to treat bacterial infections and remove the threat of resistance of bacteria to antibiotics. Phage therapy was introduced to tackle this threat. It involves using phages to treat bacterial infections, but after World War I, phage therapy was put on hold since not much information was available on bacteriophage. Recently, much work has been done on phage therapy as more bacteria have become resistant to antibiotics, and to prevent further resistance to antibiotics, phage therapy is the answer to this solution.

Similar Post You May Like

-

CFCs, HFCs and their long, troubled history

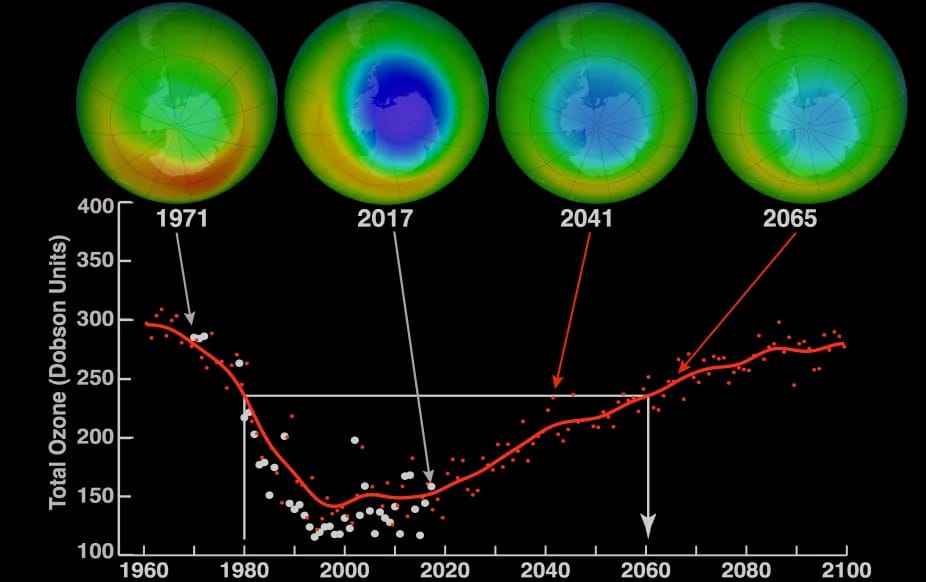

At its peak, the ozone hole covered an area 7 times larger than the size of Europe, around 29.9 million km2, and was rapidly expanding

-

The Origin of Universe: Deciding point where it all began!

Let us unravel and surf through the ideas throughout ages to understand what the universe and its origin itself was to its inhabitants across history.

-

The Artemis Program

Inspired by the Greek goddess of the Moon, twin sister to Apollo, the artimis program was named on 14 May 2019 by Jim Bridenstine.